Virtuous yard signs. The thing is, being welcoming is the rule. If you go trick-or-treating at a thousand houses you may find half a dozen that treat you poorly. The rest are happy to have you. But when you put out those signs proclaiming how welcome everyone is, you create the impression that kindness is the exception. You paint a lie, and that’s why we have so many people running around thinking that the US is such an unwelcoming and intolerant place – because people started making signs to say that “in this house is rare generosity, you are unlikely to find it elsewhere.” Talk about creating your own market. I’m sure there’s a business term for just that sort of thing – ginning up an imaginary condition for people to believe in, then offering them the only solution to it, and in limited supply.

Whatever. Enough.

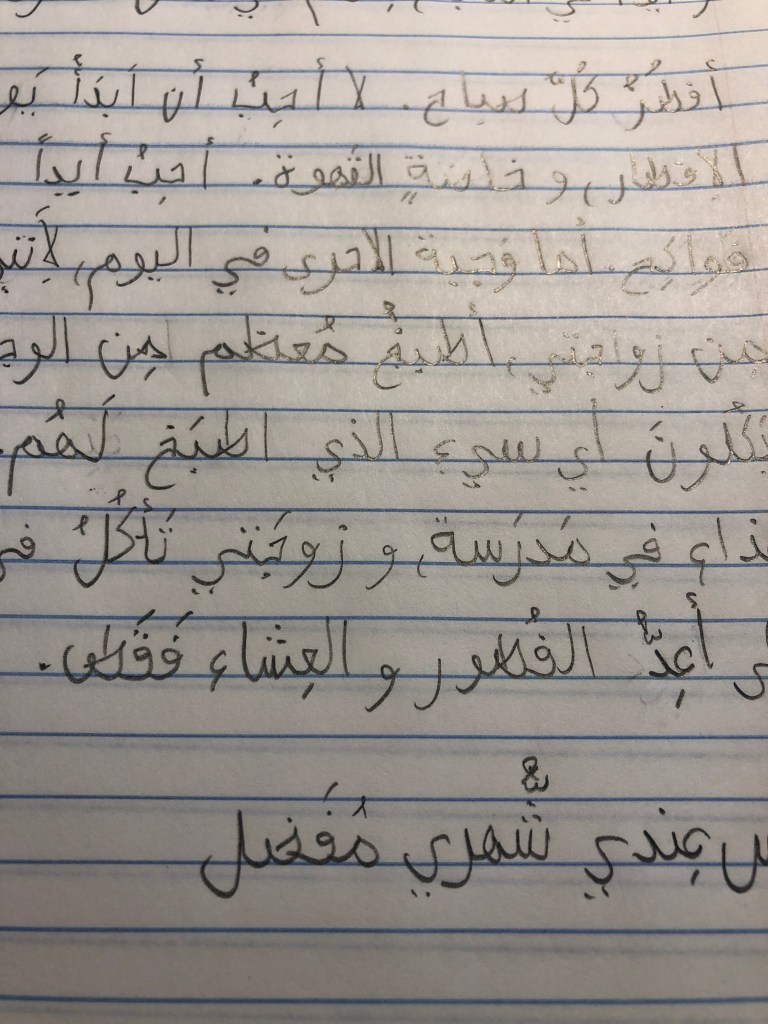

I have to take a placement exam for the online Arabic class I’ll be joining. It makes me nervous. Arabic is still intimidating, even after two years of classes and a few weeks in Morocco. And it’s been more than a year since I’ve used it, really. I’ll have to write, read, and speak. Chances are good that I’ll be rusty enough to land in a low-level course, but I don’t mind. I have time. I will say with all awareness of the seeming vanity or frivolity of it that the idea of fluency in Arabic is singularly energizing to me. Holding that odd key to another world – I want it. Even at my peak, Moroccan third week, it was still frightening and stressful and enervating, the pressure of being called upon to speak in or write in or translate from Arabic. I want it to be easy. Check back in a few years.

That brings back some good memories. It takes me too long to read and translate any of that. But man, I had better get out of that section of my photos before I get stuck deep in a rabbit hole, eating dates and drinking mint tea until my family sends out a search party. It’s gotten late here.

I wrote a couple of Morocco poems. Like this one. Here’s an earlier version. I think I like it better. The second half is better:

Show me to the old medina before the sun can warm the stones. The darkness scrubs the city bright Where the hamsas guard the homes Walk me through the old Medina before the torpid cats arise. Half their world is always dark because they steal each other’s eyes. Hide me in the old Medina among the rugs and clay tagines but don’t forget to call my name when it’s time to pour the tea. Lose me in the old Medina and seal up all the gates! I’ll learn the names of all the cats and give you half my dates!

It’s hard to get a feel for the public vibe on trick-or-treating here in West Seattle. There have been a couple of discussions about it in the comments on articles at the West Seattle blog, and it seems like a pretty even mix of “we’re taking the kids out there and enjoying the night,” and “don’t be irresponsible, stay home.” I note a (possibly meaningful) difference. It’s not 100% black and white, of course, but the two camps seem to be I’m/we’re going out, and you stay home. There are plenty of people saying I’m/we’re staying home, too, but the point is in that difference between the individual actors and the public proscribers. The argument is, of course, that the individual actors are endangering the public, so the proscription is necessary, but frankly I think that ship has sailed, for the most part, even in the minds of the frightened. There are still mumblings out there (seriously!) about killing grandmas, but I’m seeing gradual shifts in social behavior. A sense of slightly lightened tension, more people ignoring the one-way signs at the the grocery store, more people widening their social circles, that sort of thing. And hey, the parking lot at Lincoln Park is open, ahead of schedule. It’ll be packed this weekend.

We’re hosting the not-so-dead-end street for pumpkin carving on Sunday. I’ll brew up some apple cider and keep it warm on the deck. No doubt The Italian will make some pumpkin bread, The Girl Child will make some sugar cookies, neighbors will bring things, and we’ll fling gourd guts around for a while. Later, I’ll roast the seeds, and we’ll dig into some pot roast that I’m making from all that beef we panic-stocked over the summer. We nicknamed the cow from which it was carved Hector, for reasons I don’t remember. I think it was The Girl’s idea. Nobody objected.

-It’s been a year of tricks, go get your treats, Comrade Citizen!-